Two-time Olympian, Amin Nikfar, shares his Pilam and Olympic journey

Amin Nikfar, Cal Berkeley ’06, is a two-time Olympian shot putter who competed in Bejing (2008) and London (2012). Like thousands of other competitors who reached the pinnacle of athletic competition, he doesn’t have the “Sports Illustrated” story. But he does have a story of dedication, opportunity, and gratitude that doesn’t get told very often.

Amin looks back on his time at Pilam and the experience of the Olympics with a great sense of humor, and a true appreciation for the friendships he made and the opportunities he was given. He found that sports and Fraternity have the unique ability to bring people together.

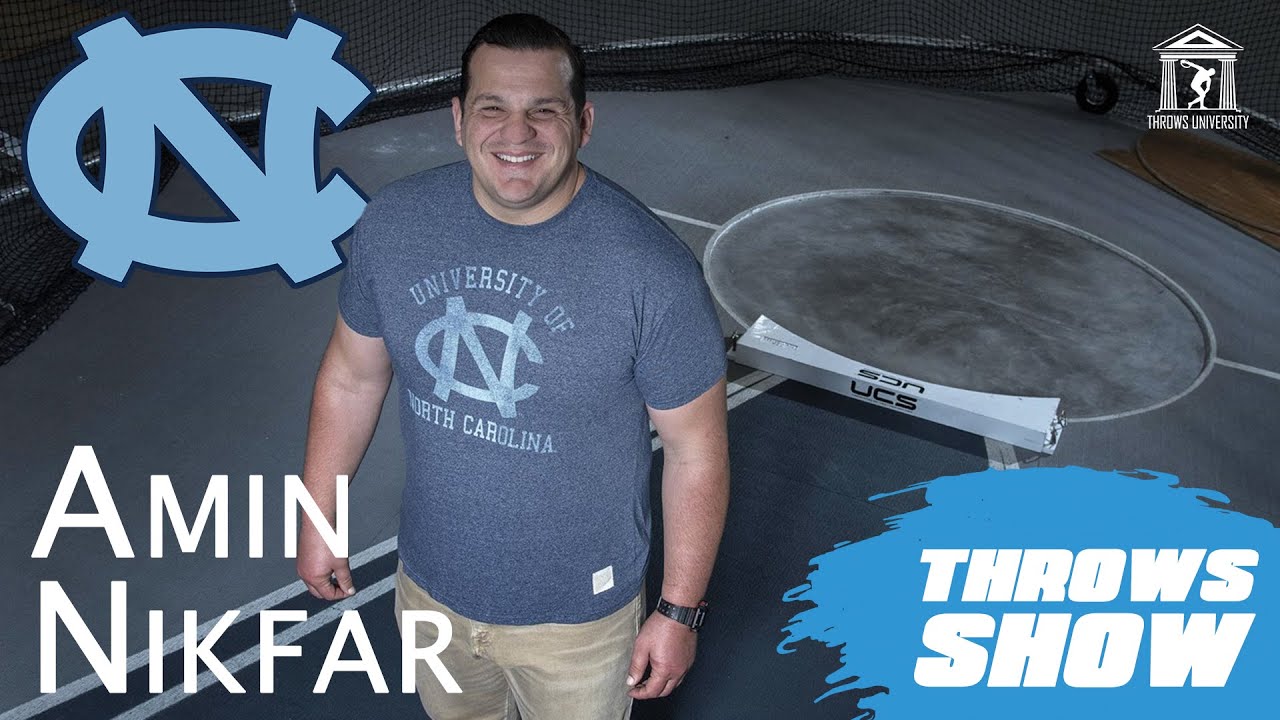

He’s currently an assistant track and field coach at UNC-Chapel Hill and a coach for the U.S. Olympic team in the hammer throw. Before traveling to Japan, Amin shared his experiences as a Pilam brother and Olympian for the Alumni History Collection Project.

Here are some excerpts from Nikfar’s Interview:

What made you want to join Pilam?

“I think of myself as an intelligent guy, but I was definitely not dialed in… not actually prepared to be there academically. One of my buddies that played football was hanging around Pilam because he had some friends there and he invited me to meet the brothers. He knew I was having a hard time with classes, and I needed some good people to be around, so I started hanging out there and it was just such an incredible fit. Not because they were all on the right track, but because they were doing better than I was. I was on academic probation at least once at Cal, so academically Pilam saved my life.”

What was it like to be a Cal Tau Pilam? What still gives you a laugh?

“The biggest thing that gives me a laugh was that they let me in, and I think they forgot that they did that. I don’t know if it was a joke or what, but my first semester I thought they were going to kick me out. The other part was for a guy that grew up in a fairly diverse area, it felt diverse. Pilam ran the gamut of skin colors and family histories. Everything from first-generation American to who knows how many generations… from a hundred percent financial aid kids to kids that are paying cash out of state. It really had a little bit of everything.”

Did the Creed have an influence on you or significance in your life?

“The biggest influence it had is that I can still recite it now. The pledge education was very strong at the Cal Tau chapter (laughs). In the beginning, when you join, it’s hard to understand the gravity of the creed. For me, as someone who coaches in higher education, it means even more especially in the current climate. It’s a big deal. When you realize that our fraternity has been doing this for a long time this way, it becomes even more meaningful.”

Many kids aspire to greatness in baseball, basketball, or football. How does one begin hurling giant stones?

“The first thing you have to do is be a bad football player. If you’re a bad football player, you can make it as a shot putter. For me it was about identifying opportunities, finding the crack in the door, and trying to burst through. I was all set to be a football walk-on at Fresno State until I got a call from the throws coach at Cal. He offered me a shot to throw the shot put, and I said, ‘if you can get me into Berkeley, I’ll walk there.’”

You went from collegiate sports to the Olympics, the highest level of international competition? How did that happen?

“The same way I got into Cal, to be honest. I was a somewhat accomplished collegiate thrower who got the opportunity to represent my dad’s country, and so we did it. There was a guy in L.A. who followed all the track and field results and saw that I was getting really close to the Iranian national record. So I started competing internationally. In 2003, I traveled to Iran and Hungary to compete. It just kept taking off from there. I got to travel the world on somebody else’s dime and change my perspective on life every time I went anywhere.”

You were born and raised in the USA, but said, “if you don’t know me it might be pretty weird that I’m competing for Iran.” What did you mean by that?

My mom’s American; my dad’s Iranian. I was born and raised in Santa Clara. But the longer I competed for Iran, the more people thought that I was born and raised there. My dad’s from Iran so, why wouldn’t I want to compete for that country? I’m proud of my heritage. I got to live the dream a little bit, and being able to connect with my Iranian teammates was a big deal. We’re all people, right. People on both sides have silly questions. I go to Iran and somebody asks me if I’ve ever seen Jennifer Lopez because I live in California. And then coming here, they ask, ‘Hey, are you worried about terrorism?’ And I’m like, why would I be worried about terrorism? I tried to live in the middle to break down stereotypes and build up some good stuff to be kind of an in-between for people that I knew in both countries.”

What it’s like competing in the Olympics?

“I don’t have the story that Sports Illustrated wants, but I have the one that doesn’t get told very often. I had a great opportunity to travel the world and compete at the Olympic games and a couple of world championships. In the track community, everybody knows each other. You see each other at the same meets. So it was a pretty cool affirmation of hard work to be at the same place, and doing the same thing as the guys who won the medals.”

Were there any nerves? Did you ever hurl before you hurled?

“This is just so terrible. When I walked into the stadium… I honestly felt nothing. No nerves, no excitement, no anger, no happiness, nothing. And I did it twice. It’s hard to explain, but really the only difference between the Olympic games and track and field championships is the year that it happens. I still felt fantastic and honored to compete and I’m still really proud of the hard work, but the biggest thing you live with, the biggest thing the Olympics games did for me was let me know that I was done competing.”

You’re coaching an American athlete for the Olympics. What are his chances?

“I coach Alex Young. He’s an NCAA champion in the hammer throw. He’s also a two time U.S. champion who competed at world championships in 2017. I think that he has a shot at a medal, but he has stiff competition, even among his teammates. All three were NCAA champions at some point. We’re going to give it everything we’ve got.”

You’re a recipient of the Fraternity’s Rafer Johnson award. Did you ever meet or interact with Rafer?

“I had a police officer friend, and his precinct was the Olympic division, where the L.A. Olympics were held. We visited the old Ambassador Hotel where Bobby Kennedy got shot. Rafer Johnson was one of the people that wrestled the gun away from the assassin. It’s really cool synchronicity that on that same weekend I met Rafer at a Rafer Johnson/Jackie Joyner Kersey track meet at UCLA. I saw him and thought, ‘Oh my God, that’s Rafer Johnson. Are you kidding me right now?’ So I just rolled right up to him and his wife, and she’s super nice. I introduced myself. ‘I’m Amin Nikfar and I won your award.’ He just looks at his wife and she’s like, ‘okay, I’ll turn around, so you can do your silly handshake.’ He was super encouraging about everything. I just met this guy, but he’s my brother. I won an award named in his honor and we had those shared experiences of the highest levels of competition. It was such a cool interaction.”

Fast facts

Nikfar coached Track and Field at the University of New Orleans, Southeastern Louisiana, Stanford, and currently coaches at UNC Chapel Hill.

Amin’s social media handle is, appropriately: @nikfarthrowfar.

Iran reportedly recruits Olympic athletes with promises of gold, “it’s so much cooler to say how many gold coins you’re going to give somebody than how many dollars.”

His Pilam nickname was “Tiny” because “nicknames have to sound good when you yell them down the street.”

Article written by Shawn Mahoney (Temple University ’92)