Harrison Dillard – Olympic Legend and Buffalo Soldier

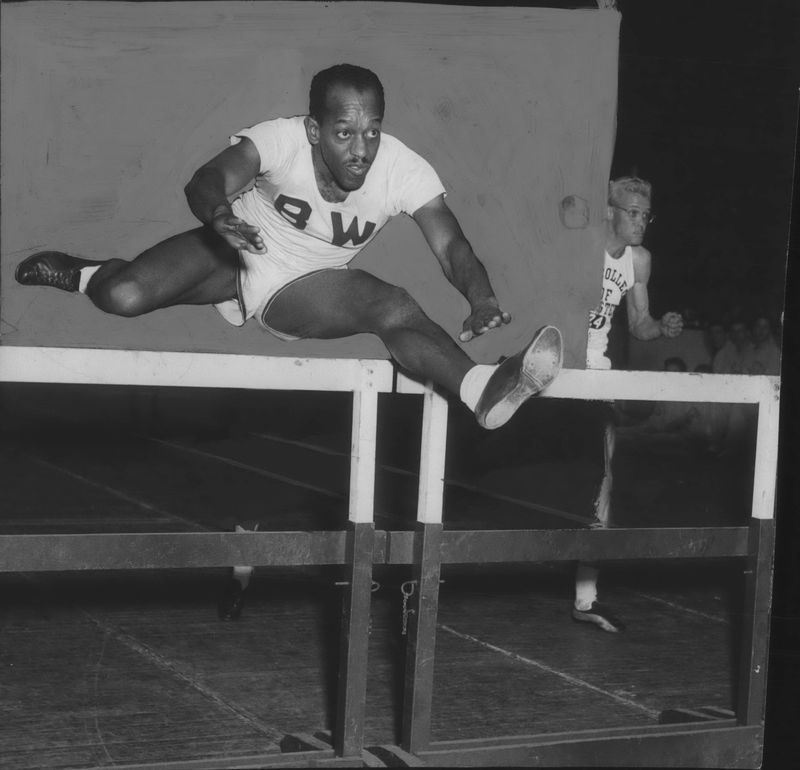

Olympic gold medalist Harrison Dillard ’49 (Baldwin-Wallace) was the “world’s fastest man” in 1948 and the “world’s fastest hurdler” in 1952. He is the only Olympian in history to win a gold medal in both the 100m run and 110m hurdles. He won a total of four Olympic gold medals.

Dillard’s athletic pursuits were postponed by WWII when he was drafted in 1943 and served for the duration of the war. When the war ended, he ran in an Army track meet and won four events. General George S. Patton, an Olympian himself, called Dillard, “the best goddamn athlete I’ve ever seen.”

Inspired by a legend

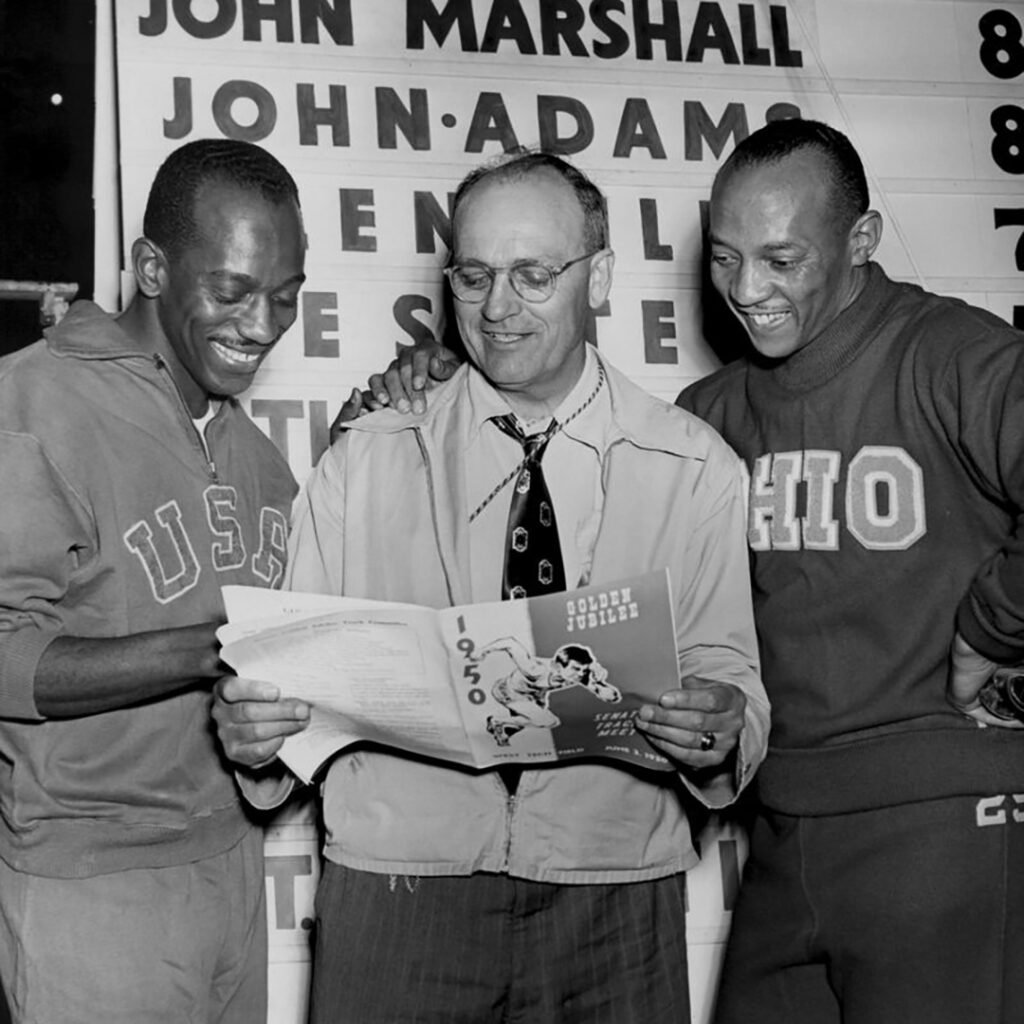

Born in Cleveland, Dillard attended the same high school as Jesse Owens. He was inspired by the legendary sprinter who defeated Hitler’s “supermen” in the 1936 Olympics.

He revered Owens as a hero, saying, “he performed his athletic feat in circumstances where they were important, by throwing the lie of Aryan supremacy right in Hitler’s face.”

In the 1940s Dillard was considered the world’s best hurdler. Known as “Bones” because of his tall, lean frame, he was a fierce competitor who loved the rivalries and friendships that occurred throughout his track and field career.

Buffalo Soldier

Just when he was hitting his stride in track and field, Uncle Sam called him up for the war effort, drafting him into the US Army in 1943.

Dillard served in the 92nd Infantry Division, known as the “Buffalo Soldiers,” a segregated unit. It was the only African-American infantry division that participated in combat in Europe during World War II.

Fighting its way through Italy, the 92nd slowly advanced, liberating towns as they went. Dillard recalled mortar fire, minefields, and the bravery of his comrades. He also remembered Italian civilians, their villages destroyed, begging U.S. servicemen for food.

With the end of the war, Dillard reflected on his service. “ when you’re going through it, all you want to do is get it over with. But I grew up physically in the service, and it taught me self-reliance and discipline. I was extremely proud to serve my country.”

Four Gold Medals in the Olympic Games

In 1946, Dillard returned to college and rededicated himself to his sport. He became a record-setting competitor, winning four national collegiate titles in the hurdles.

In 1948 after years of war, all eyes were on London for the first Summer Olympic Games taking place since 1936. Dillard said, “I was there because I chased a dream that began when I was 13-years old.”

A presumptive favorite for the 110m hurdles, Dillard disappointingly failed to qualify, but he did qualify for the 100m.

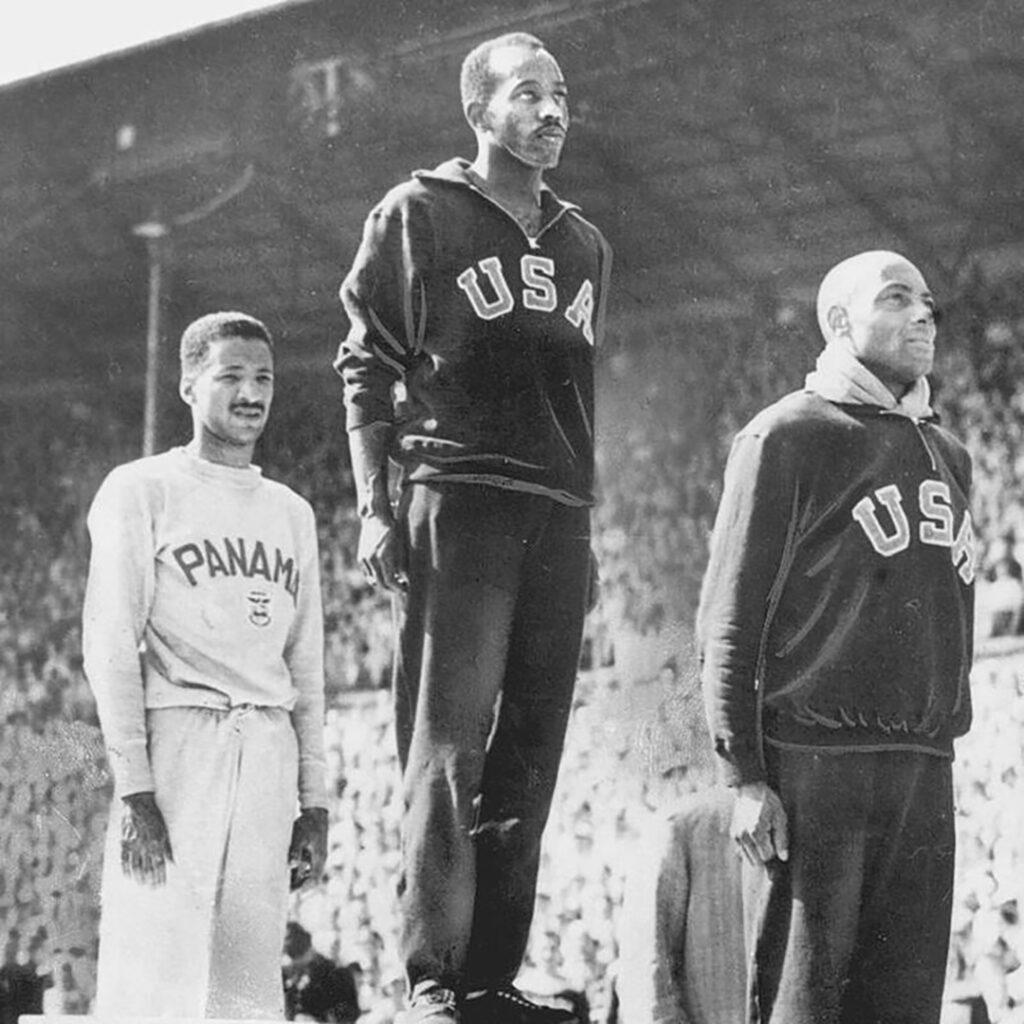

In a 100m race that ended in a photo finish, matching world-record time, Dillard captured his first gold medal. He won his second gold medal in the 4x100m relay.

In 1952, he garnered his third and fourth gold medal in Helsinki. He won another 4x100m relay, and finally captured the gold for the event that he was so highly regarded, the 110m hurdles. He reportedly exclaimed, “good things come to those who wait.”

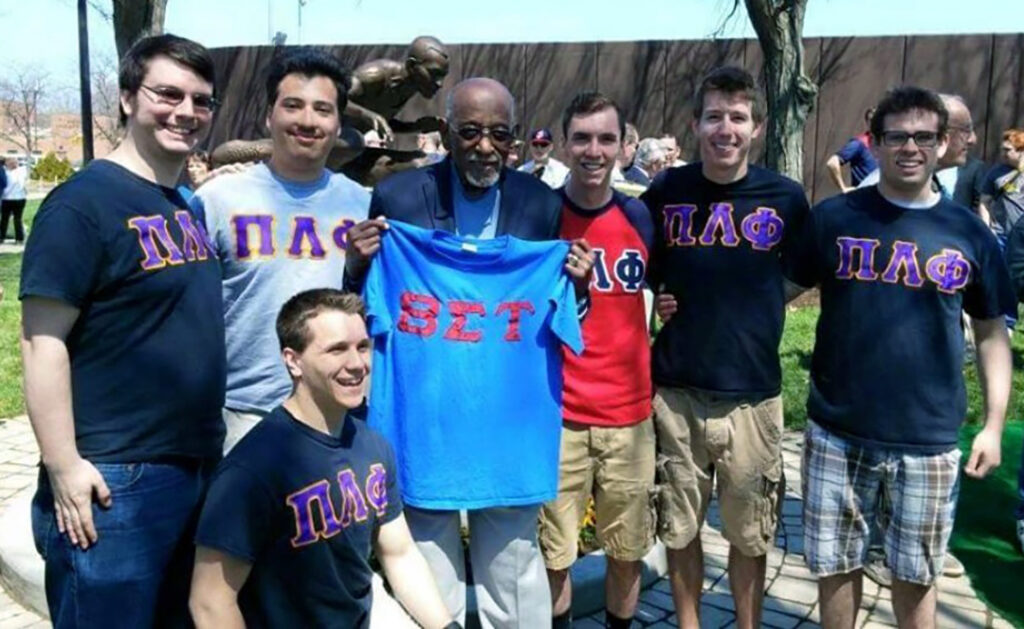

Pilam Brother

In 1941, Dillard attended Baldwin-Wallace and joined Beta Sigma Tau (which merged with Pi lambda Phi in 1960). By all accounts he enjoyed his time there, returning to the merged Pilam chapter in 1946 after he returned from WWII.

Dillard embraced the values and spirit of inclusion of our fraternity, and he spoke at the Pilam Convention in 2005 in Cincinnati.

Honoring his memory

Baldwin-Wallace still hosts the annual Harrison Dillard Indoor City Track Championships, and a life-sized bronze statue now stands as a lasting tribute to the Baldwin Wallace University graduate and four-time Olympic gold medalist.

His teammate Ted Theodore, was inspired by Dillard’s humble and generous persona and lifelong dedication to youth athletics and education. He said, “In my eyes, Harrison Dillard was a world champion by the way he lived.”

Harrison Dillard joined the Pi Lambda Phi Chapter Eternal in 2019.